L'astéroïde Hébé, image de la semaine de l'ESO

- Détails

L'European Southern Observatory (ESO) a choisi comme «Image de la semaine», l'astéroïde Hébé. Il s'agit d'un résultat d'un programme d'observation des astéroïdes avec SPHERE. Or l'Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur et l'UMR Lagrange sont très impliqués à la fois sur l'instrument SPHERE et dans les observations scientifiques qu'il permet. Benoit Carry, astronome adjoint, Marco Delbo, chercheur CNRS, ainsi que Jonathan Grice, doctorant en co-tutelle UMR Lagrange/Open University à Londres, ont notamment travaillé sur cette observation de l'astéroïde Hébé et la modélisation de sa forme 3D. L'équipe était menée par Michaël Marsset de la Queen's University Belfast.

L'European Southern Observatory (ESO) a choisi comme «Image de la semaine», l'astéroïde Hébé. Il s'agit d'un résultat d'un programme d'observation des astéroïdes avec SPHERE. Or l'Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur et l'UMR Lagrange sont très impliqués à la fois sur l'instrument SPHERE et dans les observations scientifiques qu'il permet. Benoit Carry, astronome adjoint, Marco Delbo, chercheur CNRS, ainsi que Jonathan Grice, doctorant en co-tutelle UMR Lagrange/Open University à Londres, ont notamment travaillé sur cette observation de l'astéroïde Hébé et la modélisation de sa forme 3D. L'équipe était menée par Michaël Marsset de la Queen's University Belfast.

Retour sur le passage de l'astéroïde géocroiseur 2014 JO25

- Détails

L'astéroïde géocroiseur 2014 JO25, qui a frôlé la Terre à 1.8 millions de km le 19 avril 2017, a été filmé par le télescope Ouest de C2PU, sur le site d'observation du plateau de Calern, dans la nuit du 20 avril. Le mouvement est accéléré 230 fois. © OCA-C2PU.

Changement de direction pour les UMR Géoazur et Artémis

- Détails

Nomination de la nouvelle équipe de direction de l'UMR Géoazur et du nouveau directeur de l'UMR Artémis à compter du 1er janvier 2017, pour la période du contrat de contractualisation restant à courir.

Nomination de la nouvelle équipe de direction de l'UMR Géoazur et du nouveau directeur de l'UMR Artémis à compter du 1er janvier 2017, pour la période du contrat de contractualisation restant à courir.

Le Prix Olivier Chesneau 2015 décerné à Julien Milli

- Détails

|

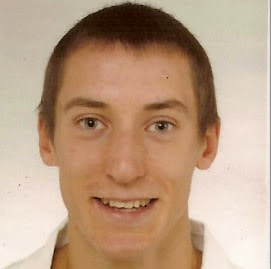

Le Prix Olivier Chesneau 2015 a été attribué à Julien Milli pour ses réalisations impressionnantes dans le domaine de la haute résolution angulaire et de la haute imagerie de contraste des disques faibles autour des étoiles brillantes. Créé par l’European Southern Observatory (ESO) et l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur (OCA), le prix est décerné en l’honneur du regretté Olivier Chesneau, l’un des membres les plus actifs et prolifiques de la communauté de l’interférométrie optique. Julien Milli est le premier lauréat de ce prix.

Le jury a été particulièrement impressionné par la profonde compréhension de Julien des différentes techniques d’optique adaptatives et sa capacité à utiliser ses connaissances pour extraire les meilleures informations scientifiques à partir des instruments NACO et SPHERE. Son expertise dans l’étude de la structure des disques protoplanétaires (disque de gaz et de poussière qui environne une jeune étoile où sont susceptibles de se former des planètes) est désormais largement reconnue et a été importante pour le début du succès de l’exploitation scientifique de SPHERE. Sa productivité scientifique et sa large collaboration dans un domaine aussi difficile a également été trouvé remarquable.

Julien Milli a achevé sa thèse de doctorat à l’Université Joseph Fourier de Grenoble, en France, en septembre 2014. Son travail sur l’imagerie des débris de disques avec les instruments NACO et SPHERE sur le Very Large Telescope (VLT) de l’ESO a été réalisé avec une bourse d’études de l’ESO sous la direction de D. Mawet (ESO / Caltech, Pasadena, USA) et D. Mouillet (Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble, France). Julien a maintenant obtenu une bourse de recherche postdoctorale à l’ESO, en observant régulièrement avec SPHERE pour poursuivre son travail sur la formation du système planétaire et l’imagerie haute résolution.

Un prix scientifique en hommage à Olivier Chesneau

|

Olivier Chesneau (1972-2014) était un astronome de talent qui a été animé et passionné par ses recherches. Il a mené un travail pionnier en utilisant l’interférométrie à longue base dans le visible et l’infrarouge.Ses résultats les plus importants comprennent l’étude des environnements proches de l’hypergéante Eta Carinae et d’autres étoiles massives, la première détection directe de disque dans les nébuleuses planétaires, la recherche de preuves d’éjections bipolaires de poussière par les novas peu après l’éruption, et la découverte de la plus grande hypergéante jaune dans la voie Lactée. Ses recherches ont souvent été largement diffusées à travers des communiqués de presse de l’ESO et duCNRS-INSU. Le Prix Michelson 2012 de l’Union astronomique internationale et de l’Institut du Mont Wilson a été décerné à Olivier Chesneau pour ses contributions majeures dans l’astrophysique stellaire faite avec l’interférométrie à longue base.

Le Prix Olivier Chesneau 2015 sera remis à Julien Milli lors du colloque international « Physics of Evolved Stars », dédié à la mémoire d’Olivier Chesneau, qui aura lieu du 8 au 12 juin 2015 à Nice, en France.

Workshop REA 2015

- Détails

Inscrivez-vous

Objectif du workshop

- Créer l’opportunité de mettre en présence les différents acteurs de l’innovation des mondes économique et académique sur des sujets phares ;

- Informer chacun de ces acteurs sur les dispositifs et méthodes dont ils peuvent bénéficier pour développer des projets innovants collaboratifs,

- Favoriser les partenariats laboratoires-entreprises et l’émergence d’idées nouvelles,

- Valoriser les ressources humaines très qualifiées.

Cible

Représentants du milieu de l’entreprise (dirigeants d’entreprise, directeur de grand groupe, managers, Directeur de laboratoire public, directeurs et chargés de recherche, jeunes docteurs, étudiants du supérieur (élèves ingénieurs, master, doctorants), consultants et autres acteurs de l’innovation.

Les 4 thèmes qui seront traités

Atelier 1 : Veille technologie et scientifique : une démarche stratégique

Par Laetitia Pineau (Cibl-Intelligence et Stratégie) & Stéphanie Godier (REA)

Atelier 2 : La propriété industrielle : à qui appartient-elle ?

Par Eric Elabd (Ventury Avocats) & Michel Aymé (REA)

Atelier 3 : Les aides financières au soutien d’un partenariat

Delphine Garcia (BPI France) & Patricia Lay (Pôle Eurobiomed) & Thierry Bonnet (REA)

Atelier 4 : Le recrutement des chercheurs au service de la collaboration

Nadine Marchandé (DRRT-PACA) & Amandine Plantivaux (REA)

Communique_de_Presse_Workshop_REA_2014-2015.pdf

Workshop "Science Cases for an Interferometric Instrument in the Visible"

- Détails

15-16 January

Nice Observatory

Contact : Philippe Stee (Laboratoire Lagrange)

Program

Participants

L’instrument MATISSE

- Détails

L’instrument MATISSE bientôt en phase de test à l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur

2015 sera une année de tests pour l’instrument MATISSE (Multi AperTure mid-Infrared SpectroScopic Experiment). Une étape cruciale qui vient récompenser les 10 années d’efforts réalisés par les membres d’un consortium européen dédié au développement de cet équipement. Les différents modules de l’instrument dont ceux réalisés par l’Allemagne et les Pays-Bas sont en train d’être réunis à l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur.

Opéré par l’ESO, le Very Large Telescope (VLT) est installé à Cerro Paranal dans le désert chilien de l’Atacama. Quatre télescopes auxiliaires lui permettent de fonctionner en interférométrie. Il devient alors le Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI). Dès les années 2000, l’instrument scientifique appelé MIDI permettait de faire fonctionner en interférométrie, 2 des 4 télescopes du VLT, puis l’équipement AMBER permis d’en utiliser 3. L’instrument MATISSE permettra de recombiner les 4 télescopes du VLT en mode interférométrie ce qui reviendra à recréer la résolution en imagerie d’un télescope géant de 200 mètres de diamètre. MATISSE est l’aboutissement de nombreuses années de recherche en physique instrumentale. Une autre originalité de l’instrument est sa sensibilité à des longueurs d’onde quasiment inexplorées de l’infrarouge dit moyen : de 3 à 13 microns de longueur d’onde. MATISSE est financé en grande partie par le CNRS, l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur et le Conseil général des Alpes-Maritimes. La Région PACA a participé à la construction des locaux d’intégration.

Opéré par l’ESO, le Very Large Telescope (VLT) est installé à Cerro Paranal dans le désert chilien de l’Atacama. Quatre télescopes auxiliaires lui permettent de fonctionner en interférométrie. Il devient alors le Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI). Dès les années 2000, l’instrument scientifique appelé MIDI permettait de faire fonctionner en interférométrie, 2 des 4 télescopes du VLT, puis l’équipement AMBER permis d’en utiliser 3. L’instrument MATISSE permettra de recombiner les 4 télescopes du VLT en mode interférométrie ce qui reviendra à recréer la résolution en imagerie d’un télescope géant de 200 mètres de diamètre. MATISSE est l’aboutissement de nombreuses années de recherche en physique instrumentale. Une autre originalité de l’instrument est sa sensibilité à des longueurs d’onde quasiment inexplorées de l’infrarouge dit moyen : de 3 à 13 microns de longueur d’onde. MATISSE est financé en grande partie par le CNRS, l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur et le Conseil général des Alpes-Maritimes. La Région PACA a participé à la construction des locaux d’intégration.

Ces performances uniques pour l’observation contribueront à mieux comprendre la formation des planètes. En effet, la technique de l’interférométrie dans l’infrarouge moyen utilisée par MATISSE permettra d’observer un ensemble de disques proto planétaire âgés de quelques millions d’années seulement et qui se trouvent dans notre galaxie. Ainsi les conditions à l’origine de la formation des systèmes planétaires pourront être observées directement. Les interactions entre les planètes et le disque seront révélées par l’étude de la morphologie des disques. Les interactions entre l’étoile et la zone interne du disque qui engendrent réactions chimiques du gaz, cristallisations des poussières, séparation entre matériaux volatiles et corps rocheux, transport radial de la matière... seront elles aussi mieux comprises. L’observation dans l’infrarouge moyen permettra de mieux analyser un ensemble de phénomènes d’importance. Vingt années après la découverte des premières planètes extrasolaires, la question des mécanismes soupçonnés à l’origine des planètes n’a pas été confrontée à l’observation.

MATISSE sera installé sur le VLT en 2016. D’ici là, toutes les pièces qui le composent seront réunies à l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, à commencer par le premier Cryostat qui vient d’être livré à Nice. Le Laboratoire Lagrange (CNRS-UNS-OCA) a conçu et dirige l’ensemble du projet et réalise plusieurs éléments dont l’optique dite "chaude" et l’informatique scientifique et de contrôle instrumental. Tous les modules seront livrés par les membres du consortium MATISSE avant la fin de l’année. L’instrument sera intégré à l’Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur où une source artificielle de photons va permettre de tester et de caractériser les performances de l’instruments pendant environ un an.

Contacts :

> Bruno Lopez, responsable scientifique, astronome au laboratoire Lagrange (CNRS-UNS-OCA), Bruno.Lopez@oca.eu.

> Pierre Antonelli, Chef de projet, Ingénieur de Recherche au laboratoire Lagrange (CNRS-UNS-OCA), pierre.antonelli@oca.eu.

Asteroids at the “photo finish"

- Détails

The Laboratoire Lagrange of the Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur plays a major role in Gaia Solar System science, as some of its members are involved in the derivation of asteroid physical properties (M. Delbo, L. Galluccio) and the prediction of asteroid observations (F. Mignard, Ch. Ordenovich). Also, P. Tanga is responsible for the whole Solar System data treatment in Gaia. For this reasons, it is clear that receiving the first test data from Gaia created a lot of excitement ! Here below, we try to illustrate the challenges specific to Gaia even on simple data such as those presented here.

We tend to think that a still picture, shot with an ordinary camera, represents a subject at a given time. But this is not always the case. In some situations, a picture can show the evolution in time of the depicted subject. This is the case, for example, of the well-known “photo finish” technique widely used in athletics to record the competing athletes as they cross the arrival line at the end of the race.

How does it work ? Simply, the camera aims only at a vertical strip containing the finish line and repeatedly photographs it at high speed. By putting all the strips together side-by-side, one can obtain the evolution of the image of the finish line as a function of time. As weird as it may sound, the CCD camera onboard Gaia works exactly the same way – by transforming the recorded star positions into times, the finish line being a thin strip of pixels on the edge of the detector.

Let’s imagine that we are looking at a number of athletes all running at the same speed on a straight track, but each of them having started the race at a different time : in this analogy, these are the stars, which drift across the Gaia telescopes all at the same velocity – given by the constant rotation of the satellite. If Gaia observes them several times, they will always appear spaced by the same delays.

Now, let’s add to these well-behaved competitors a different type of athlete, a rebel one who’s not playing by the rules, always running either much faster or much slower than the others, and not following the direction of the track lanes but drifting as he/she pleases. Each time this eccentric athlete crosses the finish line, it will be in a different position relative to the competing runners. This is how an asteroid appears to Gaia, as its motion relative to stars makes it appear always in a different position, as a function of the time at which it is observed.

This unorthodox behaviour opens up a specific category of problems when dealing with asteroid observations. The first one is predicting when – and where – Gaia will observe a given object. In practice, it’s like predicting in advance the delays of the eccentric athlete relative to the others, when on the finish line. To perform this computation, we need to have an exact knowledge of its trajectory (the orbit of the asteroid), along with the precise speed of the “ordinary” competitors (the stars). In the case of Gaia, all these pieces of information are known, but the complexity of the scanning law, which displaces the “arrival line” in non-trivial patterns, makes the task extremely delicate. Besides, there are several “finish lines” on the Gaia focal plane (at least one per CCD), so the whole geometry of the system plays a role.

The second type of problem concerns the processing of asteroid observations, especially in the case of newly detected asteroids or of asteroids whose orbit is not yet known to great precision. In fact, each time the asteroid crosses the “finish line” it will be in a different region of the sky. Only observations that are close in time can be easily linked together, as the asteroid displacement relative to its background will be small. If the observations are performed over longer time spans, the presence of several such “rebel runners” can make things extremely complex.

These various aspects are illustrated in the following pictures. The first one (right) is a test image of the asteroid (54) Alexandra, a bright moving target. It was obtained by programming Gaia in a special imaging mode. As described before, this is a “photo finish” image. It was reconstructed by moving along the horizontal axis, which is equivalent to the observer moving in time : each pixel column represents the signal present on the “finish line” (in practice : the edge of the CCD) at a given moment. In the image, the time delay between the arrival at the finish line of the bright star and the asteroid is about 1.26 seconds. A very accurate timing of each source “arrival” is the basis of the extraordinary astrometric capabilities of Gaia.

These various aspects are illustrated in the following pictures. The first one (right) is a test image of the asteroid (54) Alexandra, a bright moving target. It was obtained by programming Gaia in a special imaging mode. As described before, this is a “photo finish” image. It was reconstructed by moving along the horizontal axis, which is equivalent to the observer moving in time : each pixel column represents the signal present on the “finish line” (in practice : the edge of the CCD) at a given moment. In the image, the time delay between the arrival at the finish line of the bright star and the asteroid is about 1.26 seconds. A very accurate timing of each source “arrival” is the basis of the extraordinary astrometric capabilities of Gaia.

More important, however, is the fact that in this image the predicted position of the asteroid is very close to the observed one, only a few pixels away. Given the computational difficulties involved in this process, this is an achievement with important consequences, such as the possibility to predict well enough very close “encounters” between a star and an asteroid on the plane of the sky – these are potential sources of confusion while searching for other types of anomalies (when monitoring the brightness of a star, for example). Many astronomers want to be alerted when an interesting change occurs, not when an asteroid is just passing by !

On the other hand, other astronomers (planetary scientists !) are interested in the asteroids themselves. In fact, Gaia will observe 350,000 asteroids, providing the richest sample of precise orbits and physical properties that we could dream of. Those rebel runners, containing clues about the Solar System’s formation, are really interesting, and come in large quantities. Our capability to track their position is essential in the identification process.

The case of the asteroid (4997) Ksana (above) is more difficult, and showcases the capabilities of Gaia in detecting and identifying asteroids. Because it is very faint, it may have been confused with several stars – some not even present in current catalogues – making its identification more ambiguous. The presence of a source very close to the position where the asteroid was predicted to be is very encouraging, but only a comparison of data acquired over time can provide a confirmation.

The result is shown in (left), which represents an intermediate product of the processing itself : the preliminary positions of the sources seen by Gaia, as determined by the “Initial Data Treatment”. In these images, each point is a source and the point size is proportional to the source’s brightness. Different colours represent the stars observed during five different sweeps of the same sky region, each lasting 6 seconds, by a single CCD.

The result is shown in (left), which represents an intermediate product of the processing itself : the preliminary positions of the sources seen by Gaia, as determined by the “Initial Data Treatment”. In these images, each point is a source and the point size is proportional to the source’s brightness. Different colours represent the stars observed during five different sweeps of the same sky region, each lasting 6 seconds, by a single CCD.

The asteroid (4997) Ksana is now clearly seen moving from one sweep to the next (as indicated by the arrows). Checking the presence and motion of the object at the corresponding epoch provides a secure confirmation of its nature. A final remark : the observations are not equally spaced in time, and the closer couple of detections correspond to the source passing through the two telescopes (106 minutes apart) while the satellite rotates. A full rotation of the satellite (every 6 hours) separates the two detections in each pair.

Gaia asteroid observations will be processed using the software pipeline designed and implemented by Coordination Unit 4 of the DPAC, running at the CNES processing centre (Toulouse, France).

The data presented here are extracted from the results obtained by the Initial Data Treatment (IDT) pipeline, which was largely developed at the University of Barcelona and runs at the Data Processing Centre at ESAC.

Contact : Paolo Tanga, astronome, laboratoire Lagrange (CNRS-UNS-OCA), Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, Paolo.Tanga@oca.eu.

Source : Gaia Blog